Friday November 14th, 8pm

Join us for a very special reading…

“Indigenous people have resisted colonialism in many ways – holding fast to traditional foods, like maíz, performing ancestral dances and songs, and passing legends from generation to generation.”

Our Sacred Maíz is our Mother: Indigeneity and belonging in the Americas By Roberto Dr. Cintli Rodriguez

An introduction by the Author –

I’ve written or edited several books in my life and each of them have been special, especially since most were banned by Tucson’s school district during the state’s infamous battle in Arizona to eliminate Raza Studies, However, this one, Our Sacred Maíz is our Mother, released early by the University of Arizona Press, seems to be a little more special. Perhaps it is so because it speaks to a topic that recognizes no borders and connects peoples from across this continent, and it is a story that arguably goes back some 7,000 years.

The actual title of this book is Nin Tonantzin Non Centeotl. Translated, it means – Nuestro Maíz sagrado es Nuestra Madre – Our Sacred Maíz is our Mother. Only the English appears on the front cover. However, Nin Tonantzin Non Centeotl does appear on the title page, along with the names of 9 Indigenous elders or teachers who contributed maíz origin/creation/migration stories from throughout Abya Yala, Cemanahuac or Pacha Mama – from throughout the continent: Veronica Castillo Hernandez, Maestra Angelbertha Cobb, Luz Maria de la Torre, Paula Domingo Olivares, Tata Cuaxtle Felix Evodio, Maria Molina Vai Sevoi, Francisco Pos, Irma Tzirin Scoop and Alicia Seyler.

Each of the ancestral stories they wrote, or relate, is a treasure unto itself, each from a different people or pueblo from throughout the continent. The same thing applies to the artwork; each one is also a priceless treasure, depicting maíz in a most special way. The artists include: Laura V. Rodriguez, Tanya Alvarez, Grecia Ramirez, Paz Zamora, Pola Lopez, Mario Torero and Veronica Castillo Hernandez.

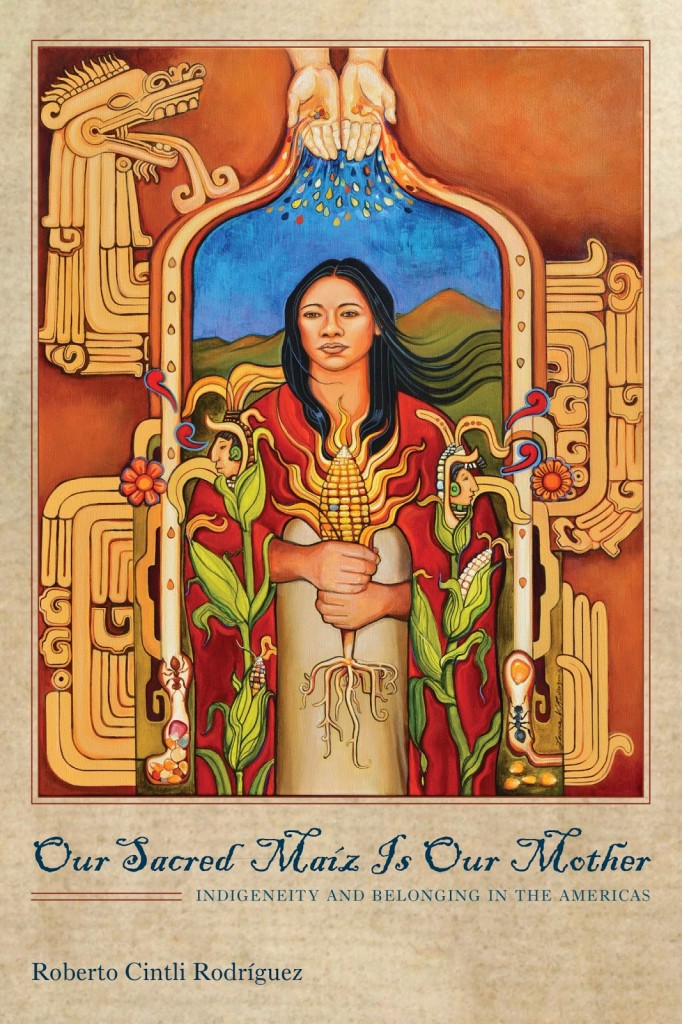

Already, I have been asked what the primary message of the book is.Each person will take away something different, but for me, my simple answer is that the title and front cover say it all: Nin Tonantzin Non Centeotl – Our Sacred Maíz is our Mother. For some, no further explanation is required.

The message resonates because it comes from somewhere profound… from a place of ancestors. Its message is: We are people of maíz. This is where we come from. This is what we are made of. This is who we are. Most Indigenous peoples form maíz–based cultures instinctively understand this message.

If you are reading this without seeing, or not having seen, the image, the front cover is a genuine amoxtli or codex unto itself, painted by Laura V. Rodriguez. It tells the ancient Nahua story of Maíz from the oral tradition and recorded in the Chimalpopoca Codex – of the ants of Quetzalcoatl – and how it is that humans received the maíz. Truly, the imagery and message are both stunning. Again, it is a story, one of many ancient stories actually, that is thousands of years old, stories that were initially suppressed during the colonial era, but now are back, not as part of an extinct culture, but as part of living cultures that exist throughout the continent, including in what is today the United States.

More than that, there is a specific message for peoples of the Americas that have been de-Indigenized, disconnected and severed from their traditions, languages and stories: despite 522 years of European presence, most remain connected to maiz culture. In particular, this applies to peoples with Mexican and Central American and Andean origins that live in the United States. And thus the message: Okichike Ka Centeotzintli or “Made from Sacred Maiz.” After all, many if not most of the peoples from these communities eat maíz (tortillas), beans and chile, virtually on a daily basis. Along with squash and cactus, these foods are Indigenous to this continent.

This is not the message brown children receive in school. It is not the message they receive in the media and it is not the message they receive from government institutions. The message in the book is that they are not foreigners, that they are not aliens and that contrary to what the U.S. Census bureau promotes, that they are not white. Instead, the message is that they are children of maíz – part of Indigenous cultures on this continent that are many, many thousands of years old.

In effect, this message was banned during the colonial era… and also in present-day Arizona… the whole country, actually. This message, in effect, was made illegal (HB 2281) by politicians who think that only Greco-Roman culture should be taught in U.S. schools. Maíz culture is the story of this continent… though in reality, it is one of the great stories of this continent (salmon, buffalo). These cultures produced not simply civilizations, but also produced values and ethos such as In Lak Ech -Tu eres mi otro yo and Panche Be – To seek the root of the truth. And it is precisely these and related values that were continually attacked during that battle to destroy Raza Studies.

But just as knowledge cannot be destroyed, neither can values and ethos be destroyed. Yes, a program was shut down, but that is temporary.

Another part of the message for this continent is, in Nahuatl: non kuahuitl cintli in tlaneplantla: the maiz tree is the center of the universe. The related message is that for those reasons, it is everyone’s responsibility to protect maiz from the multinational transgenic corporations that have literally stolen and hijacked our sacred sustenance. And it is not just the maíz that they have stolen and desecrated; they have done this or are attempting to do this to all of our crops…not just the sacred foods of this continent, but of the entire world. Because indeed we are what we eat, exposure to highly toxic (pesticides and herbicides) and genetically modified foods is highly dangerous, not simply to human beings and all life, but to the entire planet.

More than part of a de-colonial process, writing this book is part of an affirmation that as human beings, we are sacred because our mother is sacred… and on this continent, maíz is our mother.

This book is a compilation of elder or ancestral knowledge from throughout the continent, and as noted, it contains the simplest of messages, contained in both the front cover and the title.

The simple idea of this book was to counter-act… actually this book is not meant to counter anything. It is meant to affirm the thousands-of-years maíz–based cultures – to affirm that we are Indigenous to this continent – and to assert our full humanity, along with our full human rights, this in a society that brands us as illegitimate, unwelcome and nowadays illegal.

As Indigenous peoples continue to affirm: We cannot be illegal on our own continent. And yet more than that, the simple message of the humble maíz is that there is no such thing as an illegal human being anywhere. That is the primary message of the book.

Rodriguez teaches at the University of Arizona and can be reached at: XColumn@gmail.com For info re Our Sacred Maíz is Our Mother: http://www.uapress.arizona.edu/Books/bid2497.htm

______________________________

Truth Out Review: According to a legend told by elders throughout Nahuatl-speaking regions of Mexico, corn – maíz in Spanish and cintli in Nahuatl – has been a dietary staple for thousands of years. The how and why of this development has been passed from generation to generation, and, as recounted in Roberto Contli Rodriguez’s Our Sacred Maíz Is Our Mother, goes something like this: Shortly after the Creator couple, Quilaztli and Quetzalcoatl, formed human beings, they realized that their invention could not survive without eating. “Quetzalcoatl – bringer of civilization – was put in charge of bringing food to the people. Walking along,” Rodriguez writes, “Quetzalcoatl noticed red ants carrying kernels of corn. Quetzalcoatl asked one of them, ‘What is that on your back?’ ‘Cintli,’ one replied. ‘It is our sustenance.'” Throughout the text, Rodriguez tells other stories to illustrate the centrality of maíz in contemporary Mexican and Central American life, whether people are living in the United States or further south. “Maíz is who you are, who we are,” he was told time and again as he did his research. “We not only eat maíz; we are maíz.” Indeed, some of the creation stories Rodriguez tells involve attempts to fashion sentient beings from amber, mud and wood. It was only during the final attempt, we’re told – when the Creators used corn – that the effort succeeded. Not only that, as people evolved and began to cultivate maíz, they discovered its connection to “various phenomena caused by the sun, moon and universe,” among them the concept of time. This, Rodriguez writes, led to the development of a calendar and an understanding of seasons and weather.

For the rest of the review, go to: http://truth-out.org/opinion/item/26673-maiz-culture-in-the-americas-resisting-colonialism-through-indigenous-tradition

______________________________

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Roberto Rodriguez (Dr. Cintli) is an assistant professor at the Mexican American & Raza Studies Department at the University of Arizona. He is a longtime-award-winning journalist/columnist who received his Ph.D. in Mass Communications in 2008) at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. He is the author of Justice: A Question of Race, a book that chronicles his 2 police brutality trials, and co-produced: Amoxtli San Ce Tojuan: a documentary on origins and migrations. He returned to the university as a result of a research interest that developed pursuant to his column writing concerning origins and migration stories of Indigenous peoples of the Americas. His current field of study is the examination of maiz culture, migration, and the role of stories and oral traditions among Indigenous peoples, including Mexican and Central American peoples. He has a forthcoming book (Fall, 2014 University of Arizona Press): Our Sacred Maíz is Our Mother (Nin Toanantzin Non Centeotl). He teaches classes on the history of maiz, Sacred Geography, Mexican/Chicano Culture and politics and the history of red-brown journalism. In 2013, a major digitized collection was inaugurated by the University Arizona Libraries, based on a class he created: The History of Red-Brown Journalism. He currently writes for Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project and is currently working on a project, titled: Smiling Brown: Gente de Bronce – People the Color of the Earth. It is a collaborative project on the topic of color consciousness. He is also writing a memoir on the topic of torture and political violence: Yolqui: A warrior summonsed from the spirit world. His last major award was in 2013, receiving the national Baker-Clarke Human Rights Award from American Educational Research Association, for his work in defense of Ethnic Studies.

Friday November 14th, 8pm Avenue 50 Studio | 131 n. avenue 50 highland park ca 90042